Ghostwire: Tokyo Does Not Need Defending

Ghostwire: Tokyo is a flawed game. Some of those flaws jump out quite obviously during gameplay, ripping the player out of the experience if even for a moment. Some are as elusive, immaterial, and yet ever present as the yokai that confound or trap a number of spirits throughout the game’s urban environment. Some of these are perceived flaws based on an open-world design philosophy that is becoming increasingly tiresome and outdated to many in the gaming audience.

It didn’t take long, then, for me to begin spitting out words of back-handed defense while playing on stream. “It’s not great, but it’s still pretty good!” It was as if I was more afraid of over-selling the game than I was under-selling it, or reflexively trying to explain why I was having such a good time playing a game with such middling reviews. I had forgotten that there’s a reason I do not trust most game reviewers these days, particularly if they rely on numbers to summarize and assess a game’s quality.

Instead of trying to defend Ghostwire: Tokyo, as if it does not have the right to be as enjoyable as it is, I should instead be digging into what makes the game so engaging for me. Not only could this provide proper feedback to the development team by acknowledging its strengths, but it would help us better understand why some games in this tiring open-world “genre” are still able to be fun. Or, perhaps, it can simply help us understand what it is we enjoy and appreciate the most.

I can tell you right now that my primary enjoyment of Ghostwire: Tokyo is navigating around the environment. A combination of the parkour found in Assassin’s Creed and the flight of Gravity Rush, the many collectible spirits in Ghostwire: Tokyo are spread throughout the rooftops of the urban sprawl. This invites the player to observe their surroundings carefully, plotting a series of potential routes to navigate and further explore Shibuya.

There are two reasons these collectible spirits are so enticing: the first is the completionist factor. They are a thing which I can obtain and therefore I feel compelled to get more of them. This is not a shared bit of gamer psychology, but it is certainly prominent in those that grew up playing certain kinds of console games. Being a child of early-90’s side-scrolling platformers, as well as the collectible-laden Zelda and Metroid franchises, I have been hardwired since childhood to crave such things when littered across a level or landscape.

The second reason is far more universal, and that is in the practical purpose of experience points. The most common collectible in the game is also the greatest contributing factor to leveling up. After filling up dozens of the katashiro paper dolls with lost spirits, the player can transmit those collected spirits through a paranormal telephone wiring service to earn money and experience, thus allowing them to level up for more health and skill points. In other words, the player is incentivized to collect these spirits, and while many of them are on ground level or guarded by foes, they are also cleverly dotted across the heights of the city’s buildings to encourage more thoughtful exploration and navigation.

I think this is one of the most important aspects of a successful open-world game: to invoke the question “how do I get there?” from the player. In a Zelda or Metroid title, that answer may be something as simple as “after I get the right tool or ability”, but in an open-world game the gated answer may not be as obvious. If the player is capable of reaching a point with minimal upgrades but plenty of skill, then the world has been successfully designed for the player to forge their own path. No longer is the map a collection of linear obstacles with a specific route laid out, but is instead a playground for the player to plot a course of their own.

With Ghostwire: Tokyo, it seems after the first few hours the player will have all they need to navigate most of the environment. Any inaccessible rooftop or building is typically locked away for a side or story mission, which, unfortunately, is not always so clear at first glance. Additionally, it’s unclear whether the spirits are intentionally spread across the city or are dynamically or procedurally placed, either. Admittedly, this is a common issue in many open-world games, where a player may be able to explore and complete a checklist of tasks throughout an entire zone, but one or two seemingly unimportant icons cannot be reached due to a story gate blocking the path forward. It is not as true in Ghostwire: Tokyo, but that’s what makes it all the more head-scratch inducing when seemingly confronted with an inaccessible rooftop littered with hovering spirits.

Most important is that the player is not stuck doing primarily one activity, and it is the hostile ghosts and yokai wandering the now empty streets of Shibuya that the player will find themselves fighting. Or, in some cases, avoiding. I think this is one manner in which reviewers overlooked how Ghostwire: Tokyo’s open-world design effectively engages the player. Hostile prowlers make for an additional obstacle in trying to navigate around buildings while simultaneously encouraging the player to seek the rooftops rather than the mean streets. The alleyways are similarly good paths to sneak and slip through in order to avoid altercations.

However, I must somewhat agree with the critics that I wouldn’t be avoiding combat in Ghostwire if it weren’t somehow feeling lackluster. This is where it’s a bit more difficult to pinpoint what the flaws are because I don’t think it’s as simple as a “lack of combat depth”. On top of the three separate spirit elements with which to combat, the player is also capable of employing talismans and arrows in order to tackle the numerous foe and ghost types. The player can perform a perfect block to deflect certain blows and, with the right skill tree upgrades, absorb spirit energy back to fuel their elemental “ammunition”.

The use of arrows and talismans, however, feels somewhat disincentivized due to having to purchase them under most circumstances. There aren’t a lot of (obvious) spots to find spare arrows or talismans, and while money is in great supply – especially if you’re doing every side quest that pops up in the game – not all players will be willing to part with their cash so swiftly and frequently. Many of these talismans, however, are no doubt how the player is intended to make use of their different tools.

As of this writing, I have yet to try many of these strategies, but I imagine one can use the Decoy Talisman with the Stun Talisman to trap a group of ghosts and then either purge them from behind or explode them with a charged up fireball. The thicket talismans are intended to simulate shrubbery in which to hide, potentially useful for sneaking by enemies or stealthily purging them from behind.

At this stage, I am never one to criticize a developer for providing a player tools without also forcing them to make use. I don’t think it’s wrong to, say, have enemies that are only vulnerable to a certain element or weapon and therefore lock the player into a singular strategy, but I cannot help but wonder if players – and journalists in particular – have become too trained in doing things that way as to misunderstand what “depth” means in regards to mechanics.

Nevertheless, that the game supplies so much elemental energy and makes it so difficult to stealth through an area successfully seems to incentivize direct conflict using just the three elemental powers rather than making use of their complete arsenal. To that end, the powers at the player’s disposal can feel limiting, the opponents thrown their way overwhelming, and the skill tree inadequate for increasing damage dealt. Nevertheless, I would like to perhaps revisit this topic after having experimented more during my next stream or two.

Keep in mind, however, that I just listed out a lot of tools and mechanics that permeate this game, and have even explained how I’m having fun despite failing to properly use all the equipment I have been provided. Should that not communicate something of the enjoyment it provides?

So why is it that I felt like defending it? Perhaps some of it is a sense of hypocrisy. This is “yet another” open-world that has me finding collectibles, many of which dot the map with icons, revealing more and more as I clear shrines rather than climb towers. Side quests are occasional tutorials for chasing down certain Yokai that occupy the open-world, or recycle powerful foes or bosses with a slight change in their colored wardrobe.

Perhaps what makes Ghostwire: Tokyo more favorable to me is its similarities to Marvel’s Spider-Man on the PlayStation 4. After fourteen hours of gameplay I feel as if I’ve accomplished a lot on the map, having made decent progress into the story. I feel like I don’t have to keep playing for another forty hours in order to finish it off. Spider-Man was rather short for modern open-world expectations, and Ghostwire: Tokyo seems to be following the same conventions.

I view this as a good thing as it means the player can accomplish a lot of little things in the span of an hour. Or, to perhaps put it another way, the city is densely packed with activities that engage the player’s mind, be it in regards to exploring the tops of its buildings, squeezing through alleyways for hidden trinkets, or sneaking around some hostile ghosts before slapping a purging talisman on their back for a quick execution. No single activity is dragged out in Ghostwire: Tokyo, and even the multi-wave combat arenas end up having a sort of predictable rhythm to them. While in many instances this would be perceived as a potential bad thing, it also means the player can know when they’re nearing the conclusion of a fight.

There are a lot of other positive attributes that Ghostwire: Tokyo possesses, but I think the open-world exploration and the combat are two elements that have drawn that urge to “defend” the game rather than compliment it. Are these things truly handled “poorly”? Is this game really “middling”? While sitting around the 70-some percentile range of review scores is hardly “bad”, it also misrepresents and mischaracterizes the imagination present in the game’s design.

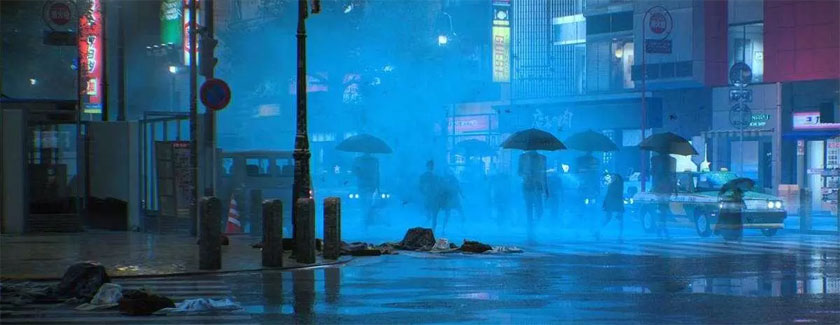

I think Ghostwire: Tokyo deserves better, and perhaps I feel so because it’s not the sort of game that your more mainstream audience will immediately latch onto. Despite seeming to dabble in standard open-world gaming tropes, there are a lot of cool ideas I continue to run into as I progress through the game. It sits somewhere around the Yakuza style of urban exploration, where a foreign Japanese city is made all the more mythical by the supernatural events occurring. Looking at the clothing scattered across the street, sometimes in clumps on a park bench or piled at the bottom of an escalator, it tells a story of a city typically crowded yet now silent, save for the moaning of grudge-laden spirits from the Other Side.

We’ll see what I think after I finish the game, and perhaps after I’ve experimented more with its combat options. In the meantime, I want to stop feeling so wishy-washy when describing why I enjoy the game, almost as if I shouldn’t be having a good time. I can think of nothing more insulting to the hard work of Tango Gameworks than to compliment their game with guilt and uncertainty in my voice.